Blood leaked onto my clothes on the first day of our family vacation in North Carolina. As always, I was melancholy, annoyed, and even surprised that blood gushed from my vagina without permission, my butt and legs cramped, my head and abdomen ached, and my pelvic area swelled. Years ago, each month I bled meant an empty womb but now I have a family and the blood still torments me.

As usual, I was unprepared for this unwanted monthly event and had forgotten my cup at home in Utah. I was bleeding into my underwear (the rolled-up toilet paper I placed there was stuck between my butt cheeks, doing nothing but making me more uncomfortable) as I told my kids why we were inconveniently going to the store. But then my sweet twelve-year-old daughter happily exclaimed that she had packed tampons in her luggage, “we are here for a month, mom,” she said wisely. She didn’t forget. She hasn’t learned to hate it yet.

Still, after 23 years of monthly menstruation, I hate it and I forget it. I ignore my body and its cycles. My body routinely sloughs my uterine lining, letting the past go literally and figuratively, and I never listen. Cyclical bleeding is powerful imagery, and yet, I have never thought about my period as anything other than a marker of fertility and a painful inconvenience until now.

My newly menstruating daughter shows me that menstruation can be layered with meaning, rich with potential rituals of beginnings and endings, of change and acceptance, of bleeding and suffering, of thresholds and new life. If I pay attention, menstruation is a natural, feminine ritual.

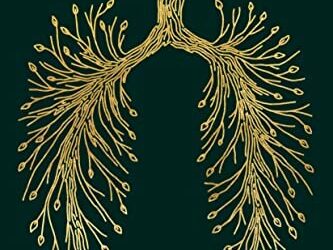

“For the life of the flesh is in the blood” (Leviticus 17:11). How have I never connected my blood with the blood and life of theology? How have I never related my cyclical suffering and bleeding with the suffering and bleeding of scripture? “For it is the blood that maketh an atonement for the soul” (Leviticus 17:11) and women know blood. The female body is Jesus’s body with its waters rushing out, its shedding of blood and holes, its death and life, its birth and cycles, its suffering and knowing. Women’s menstruation is life and soul.

And yet, menses has not fit into my life because I have designed my life not to fit it in. Patriarchy with its male pronouns and its lines of succession through sons has left no room for female symbolism in my mind. No room for me. I have lived a patriarchal life and celebrate patriarchal rituals and forget who I am; I forget that I witness blood, touch blood, and bleed for “the life of the flesh” for days every lunar month. Next month, like my daughter, I will be prepared, conscious of my body’s monthly bleed.

Because, joyously, my body’s bloody ritual is not controlled or created or given to me by ancient men – it happens without obedience, without choice, without words or permission or privileges or money or ceremony or worthiness. It is all mine. I have been aching for feminine rituals and here it is in my divine body performing without me. Why haven’t I ever made it symbolic? Important? Meaningful?

Maybe because I do not know the traditions of my mothers. My little twelve-year-old self kept my maturation a secret from my own mother. A secret from myself. If we ever knew the traditions of our mothers, they have been hidden, ignored, hated, and shamed away into the darkest corners of history.

Consequently, I know and study the traditions of our fathers. These traditions and stories and symbols are practiced and performed in temples and churches and homes and governments and everywhere from the beginning of written history. Traditions of blood have been turned into water, traditions of childbirth have been erased into lists of men begetting sons, and traditions of menopause, life after blood, have been eradicated.

In the primary song “Follow the Prophet,” a song celebrating the traditions of our fathers, verse four exuberantly preaches about bringing life and children into the world; however, somehow it does not mention a single woman. It does not mention her body or her prayers or her blood or cycles or sacrifices. It doesn’t even allude to them. It literally says that “Isaac begat Jacob.” Our songs and scriptures and ceremonies forget the women whose wombs were full and especially the women whose wombs were emptied. The ones as baren as men. “So the Bible tells” (or doesn’t tell) our Christian traditions. The visceral is cleaned up, sanitized. And I am left confused and forgetting with blood on my fingers.

But no more excuses. I am not limited to the English bible rituals and stories. As a woman, I already have my own rituals within my body. Women’s periods represent death and birth, earth and science, mystery and magic, suffering and rhythms; and then they drip away and menopause crawls into our bodies. The ritual of blood and body is fluid and changing. It is feminine. And I want to cry in relief and wonder for women’s changing bodies. Perhaps, the traditions of our mothers are written: they are written inside of us.

Tragically, I forget my period but remember to attend the clean, white temple; unfortunately, I hate my blood dripping down my legs but drink the clear sacrament water every week; painfully, I sing about fathers begetting sons and ignore the women who bled and pushed and carried them in their wombs; devastatingly, we pray to a father and not a mother: “so the bible tells.” These are the traditions of our fathers, clean and white. But the traditions of our mothers and aunts and friends are here too, bloody and dark and rhythmic. No one can stop them. And they are not hidden; they are made manifest every month when I symbolically bleed onto the fabric of my no longer white garments.

Leave a Reply