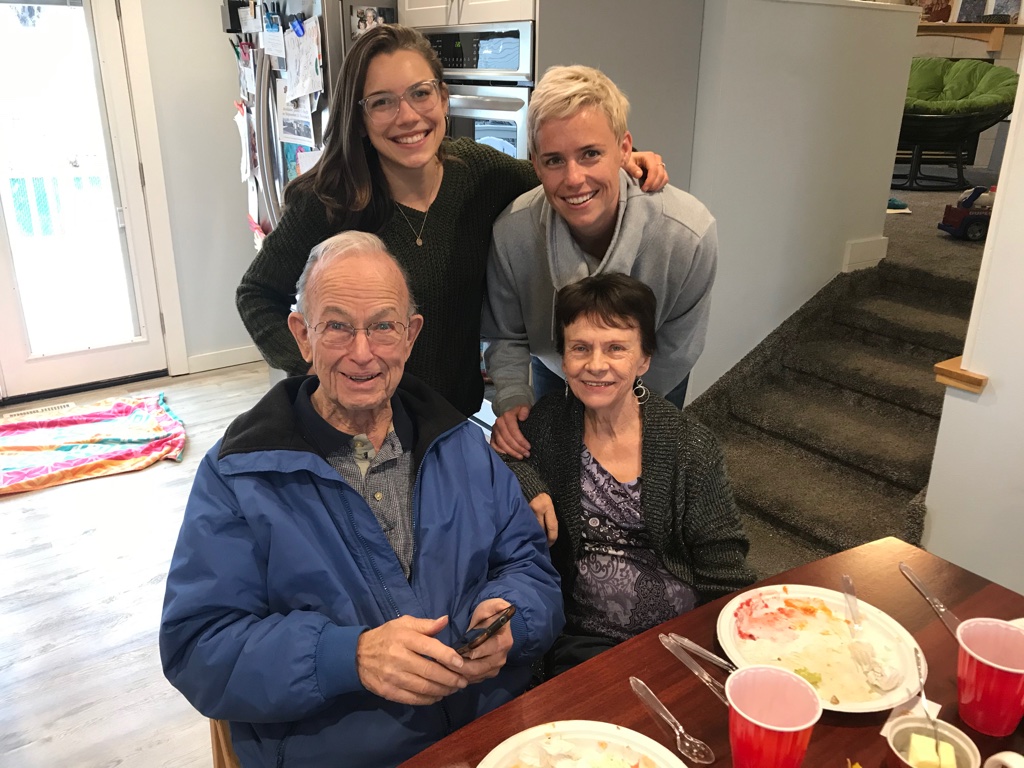

When I was young, I examined the blue veins that spread under my grandmother’s pink, brown, and white splotched skin and traced her exposed metacarpal bones with my index finger. Those old hands rubbed my back while she sang love songs to me in her shaking voice. I would play with the folds of velvety skin on her cheeks and neck; that beautiful old woman. My grandmother’s hands are colorful: pink, purple, blue, white, red, and brown. Her white hairs glisten in the sun and her gentle hands cling to someone’s arm as she slowly walks through an emerald path of trees. She used to be young with fewer colors and wrinkles on her skin. More flesh on her bones. But I don’t know that woman, that girl she remembers, all I know is my wrinkly, wise, wonderful Grandma Emma.

I’m no longer young and not yet old; I’m shave my lip and pee a little when I cough middle-aged. Recently, I bought a full facial kit: resurfacing toner, illuminating serum, and gentle exfoliating cleanser. However, it would be more accurate to declare that I bought the participial adjectives – the ideas of resurfacing, exfoliating, and illuminating my skin; the idea of not getting old is what I bought. There are so many aesthetic options for looking young: hair extensions, veneers, artificial eyelashes, waxing, breast augmentation, hair dyes, and makeup tattoos. A very popular option is to inject botulinum toxin around the eyes, causing flaccid paralysis to keep skin from wrinkling. No wonder I panic when one hair grows from a mole that once was a beauty mark, or when those silver hairs spring from my scalp like seedlings: marketing shrieks at me to remain young.

I’m afraid of looking old so I buy hopeful adjectives that are magically infused into serums, toners, and creams that I know don’t work. Ridiculous. When I smile, my eyes crinkle and when I concentrate, my eyebrows squeeze together; no number of adjectives will resurface my wrinkles. I’ve been young, now I’m growing old; chasing my mom through time like she chases her mother, my colorful grandmother. Wrinkles are the price I pay for not dying. I remember my mom pulling her skin back to her scalp, smoothing out her wrinkles, or saying “you’re giving me grey hairs,” like it was a bad thing. But I loved how her white strands reflected the sunlight like diamonds hidden in her muddy hair. It meant she was alive.

Plump skin rolls around my daughter’s thighs and neck as she walks slowly, holding my hand for balance. She is a delicious pink. My greatest hope for her is to live, to grow, to become old. I want to watch her grow old. She already traces the purple veins that bulge from my dry-skinned hand like a map of the desert and knows the wrinkles on my face when I smile. She wants to grow old with me, too. Aging doesn’t happen to everyone, but death does. My daughter’s fresh toothy grin reminds me that I do want to get old. The alternative is definitive.

All old things have been young, but not all young things become old. Being young is inevitable, becoming old is a miracle. Being born is also a miracle, but getting older is inevitable until it’s over. Our lives ride on different human rhythms; sometimes we are slow and learning, sometimes we are slow and forgetting; sometimes we are steady, quick, and healthy; sometimes we are sickly and wavering; sometimes we are the creator, the designer, the maker; sometimes we are the watcher, learner, and listener; sometimes we are plump and fleshy; sometimes we are saggy and bony; sometimes we are the doer, sometimes we are the wait-arounder; sometimes we live, and sometimes we die.

Here is a story about living. My grandmother relaxed on a reclined chair at the dentist’s office with headphones on while she watched a cooking show on the ceiling. Her mouth was open, being cleaned by a young woman in green scrubs. My grandmother had just returned from Cambodia, her third senior service mission, where she had missed a few scheduled cleanings.

When the dentist came in, my grandma took the earphones off her curly white-haired head.

“Good news, Mrs. Haight, you don’t have any cavities,” the dentist said. My grandma visibly relaxed before he said, “I’m curious, why haven’t you ever had braces?”

“Oh,” my grandmother said, “I just never thought about it, I guess.”

“I don’t see teeth this bad anymore. You should have gotten braces sooner, but I will recommend some really great orthodontists to you,” the stranger said.

When my grandfather drove her home, my grandmother was unsmiling and small. Surprised, my grandfather assumed she had cavities that needed filling. But she said no. Pain? No, she said. For days my grandmother didn’t smile. Her usual sunshine self was snuffed.

Finally, my grandfather sat her on the bed and told her to tell him what was wrong. She held her face in her hands as she wept the story into the room.

“Why have I never thought about my teeth?” she cried, “I should have gotten braces years ago. I didn’t know my smile was ugly.”

My grandpa reached across the bed and held his old wife in his aged arms.

“Your smile is beautiful,” he said.

“No. It’s not. My teeth are so crooked, the dentist was right,” she said.

Holding my grandmother’s face in his hands, forcing her to look him in the eyes, he said, “No. He was not,” tears traced the wrinkles down his face, too. “Everyone that looks at your smile sees your love. Think of your grandchildren’s faces when they see you. All they see is you, their grandmother, who smiles every time she sees them. Think of the way their faces light up when they see yours. They don’t care if your teeth are crooked, all they want is you. I don’t care if your teeth are crooked, all I want is you.”

All I want is wrinkly, saggy, crooked teethed you. Maybe there is more to being human than looking young. My grandma still smiles her crooked toothed smile; that dentist was wrong – her smile is the most beautiful, old, imperfect thing that lights up the faces of those who know her. That dentist was distracted by the artificial and aesthetic current ideal. He didn’t see the cleft palate she was born with, the years of occupational therapy that taught her to talk when she was five, the life within her glowing crooked smile, the seven children, 35 grandchildren, and 35 great-grandchildren who love her face. The dentist was distracted by cultural perfection and missed the deep history of her overlapping teeth.

When I am distracted by the cultural perfection of women, I miss the deep history I am creating with the grooves and rhythms of my body. My daughter is young with her fleshy plump pinkness, my grandmother is old with her saggy exposed colorfulness, and my mom and I are sliding somewhere in between. All old things have been young, but not all young things become old. I long to hold oldness and youngness and everything in between in my hands; I long for myself. Being here. In this moment. Not with the regimen of distracting participial adjectives, but with my daughter, my mother, and my grandmother. With my body just the way it is right now because it will change tomorrow if I’m lucky enough to live one day older.

Leave a Reply