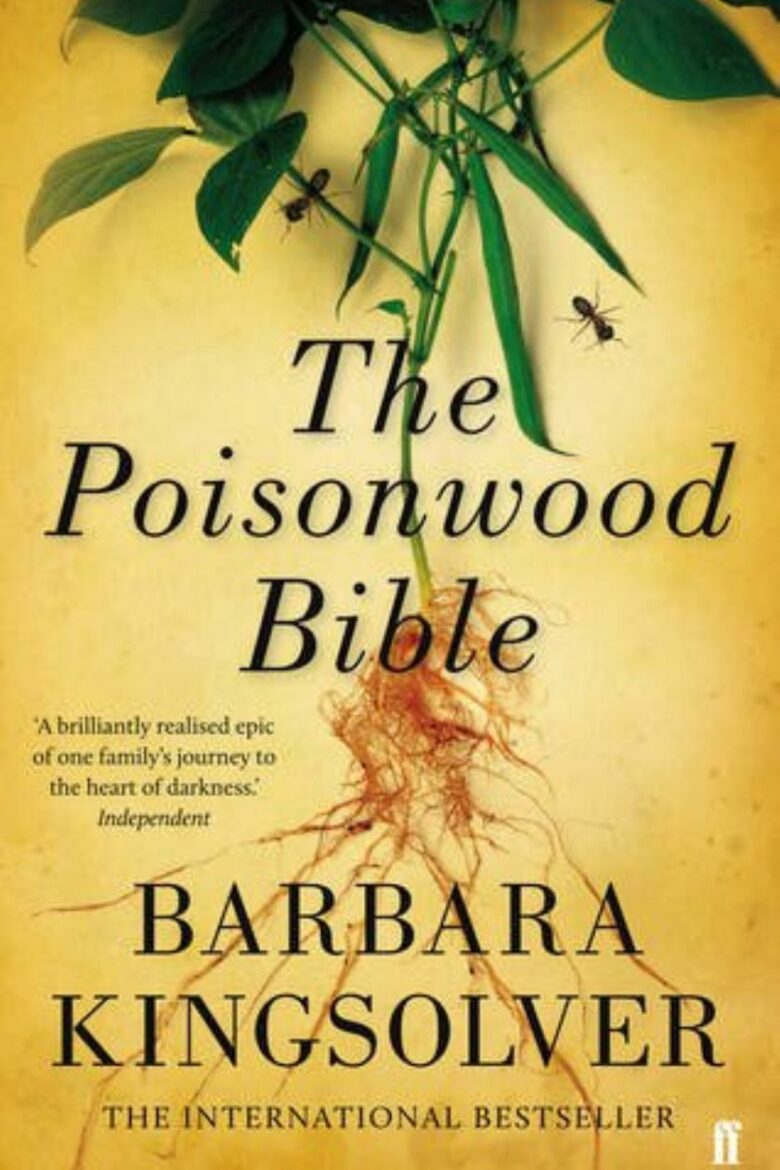

“Watching my father, I’ve seen how you can’t learn anything when you’re trying to look like the smartest person in the room.”

– Leah, pg 229

This novel has been with me for years. I read it in my Literature by Women class. The Poisonwood Bible was my first exposure to various points of view divided by chapter; the varied voices of the five Price women have continued speaking to me over the years. Their individual perspectives of their family’s experience as uninvited Christian missionaries in the Congo still haunts and reminds me that truth is fractured – each participant in life takes a piece.

One of the most striking metaphors from the book is the tomato seeds Father Price brings to the Congo in an effort to solve the crisis of starvation sweeping through the country. Ignoring the experiences of the villagers, he plants the seeds and watches healthy vines grow into massive green plants, believing that he is right and the natives are wrong. But there are no bees to pollinate and the plants bear no fruit, feed no hungry mouths. And so it is when we think we have the answers and do not listen.

“‘Diamonds, yes,’ Anatole said. ‘Also cobalt and copper and zinc. Everything my country has that your country wants'” (229). . . he speaks of country like it’s a hungry thing but then says, “That is Congo. Not minerals and glittering rocks with no hearts, these things that are traded behind our backs. The Congo is us” (231). The semantics of country implies resources, economy, things. But The Poisonwood Bible taught me that country is people, individual humans. We do not own the land.

The novel takes place in 1960’s Congo but parallels our world today; do we speak of our country and other countries like they are things? When we do this, when rhetoric reaffirms countries as things, we ignore the children, lovers, and heroes; we forget the violence that humans experience when treated as things and the destruction of the world when we view land as a commodity. Kingsolver’s novel blurs physical borders and embraces the experiences that divide us. Listen, it says, we are all human.

Leave a Reply