“The soul knows who we are from the beginning.”

Plato

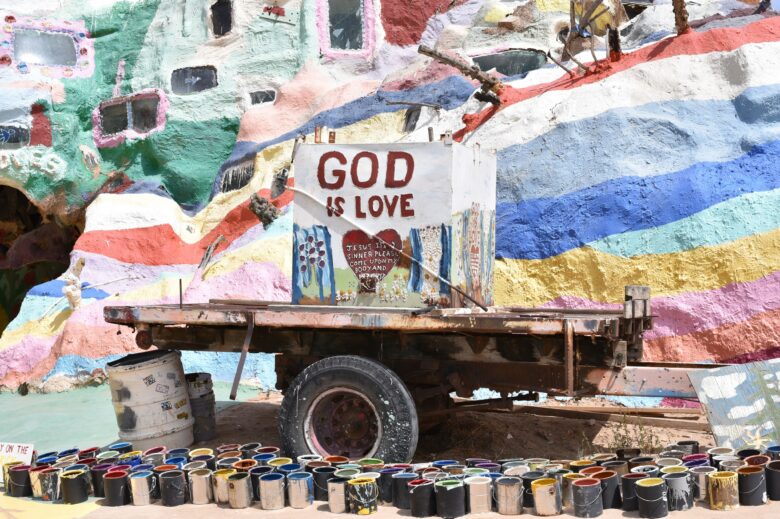

In seminary my freshman year of high school, many things about church doctrine didn’t make sense to me. But when we read 1 John 4:8, “But anyone who does not love does not know God, for God is love,” all truth, wonder, and acceptance collided within my fourteen-year-old soul. These words made sense.

The idea that God is love brought clarity to my struggles. I struggled to accept my oblivious, mess-making, neurodivergent, piano-genius little sister. I struggled with alcohol, sex, and friends while guilt and self-hatred ripped and tore through my body causing me to drag plastic knives across my wrists until the burning welts bled with relief. But maybe that judging, disappointed God who couldn’t be around me because of my sins was only a figment of my teen dysfunction. Maybe God was love.

The scripture verses in John reminded me that I often felt love in the wind that cooled my cuts and accepted me for who I was; I felt love when my young women’s leader told me I asked good questions or when my mom played the piano for me while I sang or my baby sister sat on my lap while I read. God is love. God IS love.

Suddenly, I knew God. I recognized the times God healed and saved me. Suddenly, I realized that because I had been taught to love my siblings, my grandparents, my aunts, uncles, parents, cousins, and friends, I knew God.

“God is love, and all who live in love live in God, and God lives in them” (1 John 4:16). These verses were blowing my mind. I didn’t need to punish myself to know God? I didn’t need to hollow myself out, scrape my ugliness out with the branding iron of sin? Those moments of love, the hard work of loving my sister, the magical moments of my grandmother holding my face in her hands and weeping with love for me, those moments in the wind when I realized the earth loved me even though I was a sinner, those moments meant that God lived in me?

The realizations and connections that were pouring over me like waves stunned me to tears. I sat at my desk, surprised by the tears that made dark circles on 1 John. I knew with my whole heart that dear John was right. God is love, I knew God, and God miraculously lived in me. And not just me, I realized, in every person who lives in love. I looked around me and saw Gods in the disparate Provo High seminary students.

I ran my finger over the words: “God is love.” We were given a few minutes to write about the verses we read, but I had not been paying attention to the lesson plan and when it was time to share and discuss, the class discussed apastocay and spiritual darkness. The seminary teacher, who has a difficult job, made a list on the board: “how to know when someone is experiencing spiritual darkness.”

The juxtaposition between my reading and the seminary lesson was jarring and I started to become upset as a few classmates, directed by the teacher, were writing and discussing people who were “walking in darkness.” I knew I walked in darkness, I was one of those people they were discussing. I also knew that many of my friends who were not LDS but who lived in love were being condemned by these verses that I had not read or seen, the same scriptures that healed me were also condemning my friends, my brothers, my aunts and uncles – some of the most loving people I had ever known. Just moments ago I had known God was in them.

I raised my hand, “It says right here, that God is love, and it says it again, that God is love, I think that is the most important thing. That means that whenever we feel love, God is in us.” I bumbled about getting more and more upset, not realizing that I was making the seminary teacher more and more upset as well.

“You need to be careful,” he warned.

I don’t remember exactly what the seminary teacher said but I remember it crushed me and involved the word “antichrists.” It crushed me enough to cry silently in a bathroom stall after class. It crushed me enough to tell my mom that I didn’t belong in seminary. It crushed me enough that I still remember that experience and my heart aches for everyone in that room.

It surprises me now that I didn’t question the personal revelation I received when I first read those words to myself and felt God bursting within me. I questioned the man teaching the class. I didn’t question God’s love for me, the God within me, or the love within everyone else. I recognized that what was being taught in seminary was not my experience, I recognized that I didn’t belong.

I’m not saying that disagreements or differing perspectives should not be shared and kept; belonging is so much more complicated and nuanced than that. I’m saying that as a young, immature girl, I was developing and recognizing the foundations of my faith.

I didn’t go to seminary again until my senior year of high school when I loved it. I loved hearing how people prayed and what they prayed for, hearing stories where God appeared, learning how others read scriptures as their sacred texts, and being forced to question myself and preconceived notions. My seminary teacher was missing a thumb and made me laugh all of the time. When I disagreed, I didn’t flee, and usually, I didn’t feel like voicing my disagreements because I was curious and appreciative of the people around me like I hadn’t been before.

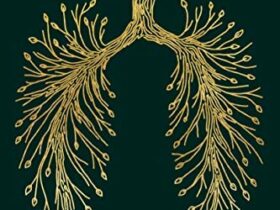

The testimony inside of me was like an unidentified sapling, it had roots that held it in my heart, that pulled and nourished my soul, roots that grew and expanded with my personal experiences and the meanings I derived from those experiences. Also, like a tree, there were outside sources that influenced its growth. Gospel discussions, other people’s opinions and experiences, scripture study, conference talks, etc. were like wind and rain and elements that changed or broke branches or fed and pruned my budding tree, but it was always mine.

That seminary teacher my freshman year made me feel like my testimony was his seed to plant in my heart, but it wasn’t. I didn’t even know my sapling was growing until I felt it when I read those words, “God is love,” and I recognized its wispy little shape and the deep roots that made me. “Ah,” I thought, “there you are, that is what you look like.”

We all have trees of meaning inside of us; each seed is a unique compilation of experiences, DNA, and nutrients. When did you first recognize yours? Was it when someone else was telling you what it should be and you realized that wasn’t yours at all? My tree is made of love. All meaning for me comes back to love. Love that looks like inclusion, acceptance, listening, and story form my sapling’s branches and roots. So when that seminary teacher was telling me that my faith should look like obedience and conformity and exclusivity, I didn’t recognize those at all in my tiny little sapling. Those ideas swirled around inside of me blowing my tree around, too much for my little soul to bear.

But now, my tree can take wind. Sometimes, other people’s ideas are like sunshine and spring for my little tree and sometimes like a tornado, one time it was like an axe that cut it down, but the roots were still in me. Often we can choose the environments we allow our trees to thrive or die in and sometimes we can’t. When people stop practicing with us, I like to think it is because their tree was being blown around or hacked away by its environment – I have learned that the only way to recognize our soul tree again is to find a new environment where we can say, “Ah, there you are, that is who you are.”

Many people suffer and have left the church because of seminary teachings and the forced, uncaring control of force planting trees in people’s hearts. No one should do that to another person, and when we try, we cause scars in the landscape of their souls. The goal should never be to force people to maintain practices or membership or rules, it should always be for them to plant their own trees. For us to nurture them even if they look impossibly different from our own. If these people find that their trees look queer, it could mean that they need different environments, different outside sources, different nutrients.

What is your sapling made of? What feeds it? What hacks at it? In what environments does it thrive?

Photo by Olga DeLawrence on Unsplash

Photo by Emmanuel Phaeton on Unsplash

Photo by Kasturi Laxmi Mohit on Unsplash

Leave a Reply